University of ancient Taxila

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Pakistan |

|

| Timeline |

| Ancient

|

| Classical

|

| Medieval

|

| Early modern

|

| Modern

|

| History of provinces |

|

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Punjab |

|

| Prehistoric

|

| Ancient

|

| Classical

|

| Medieval

|

| Colonial

|

| Post-independence

|

| History of South Asia History of Pakistan History of India |

|

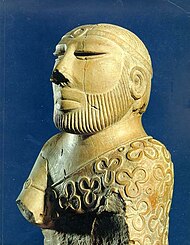

The University of ancient Taxila (ISO: Takṣaśilā Viśvavidyālaya) was an ancient higher-learning institution in Taxila, Gandhara, in present-day Punjab, Pakistan, near the bank of the Indus River. It was established as a centre of education in religious and secular topics.[1][2] It started as a Vedic seat of learning;[2] while in the early centuries CE it became a prominent centre of Buddhist scholarship as well.[3][2]

Early history of Taxila

The earliest archaeological remains of the site go back to 6th century BC.[4] It became the capital of the Achaemenid territories in northwestern Ancient India following the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley around 540 BCE. Taxila was at the crossroad of the main trade roads of Asia, and was probably populated by Persians, Greeks, Scythians and many ethnicities coming from the various parts of the Achaemenid Empire. It was abandoned in 5th century CE.[2][5][6]

University

According to John Marshall, Taxila emerged as a centre of learning after the Persian conquests due to its geographical position, "at the North-Western gateway of the subcontinent," and the "cosmopolitan character of her population."[1] It started as a Brahmanical seat of learning.[2] According to Frazier and Flood, the highly systemized Vedic model of learning helped establish large institutions such as Nalanda, Taxila and Vikramashila.[7] These universities not only taught Vedic texts and the ritual but also the different theoretical disciplines associated with the limbs or the sciences of the Vedas, which included disciplines such as linguistics, law, astronomy and reasoning.[7] The university was particularly renowned for science, especially medicine, and the arts, but both religious and secular subjects were taught, and even subject such as archery or astrology in hindu world.[1]

According to John Marshall, "In early Buddhist literature, paricularly in the Jatakas, Taxila is frequently mentioned as a university centre where students could get instruction in almost any subject, religious or secular, from the Veda to mathematics and medicine, even to astrology and archery."[1] The role of Taxila as a center of knowledge grew stronger under the Maurya Empire and Greek rule (Indo-Greeks) in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE.[1] In the early centuries CE it was a prominent centre of Buddhist scholarship as well.[3]

It was not a university in the modern sense, in that the teachers living there may not have had official membership of particular colleges,[8][9][10] in contrast to the later Nalanda university in Bihar.[10][11][12]

The destruction by Toramana in the 5th century CE seem to have put an end to the activities of Taxila as a centre of learning.[13]

Teachers

Influential teachers who are said to have taught at university of Taxila include:

- Pāṇini, the great 5th century BCE Indian grammarian[2]

- Chanakya, the influential Prime Minister of the founder of the Mauryan Empire, Chandragupta Maurya, is also said to have been teaching at Taxila.[14]

- Kumāralāta, according to the 3rd century Chinese Buddhist monk and traveller Yuan Chwang, Kumāralāta, the founder of Sautrāntika school was also an excellent teacher at Taxila university and attracted students from as far as China. [15]

Students

According to Stephen Batchelor, the Buddha may have been influenced by the experiences and knowledge acquired by some of his closest followers in the foreign capital of Taxila.[16] Several contemporaries, and close followers, of the Buddha are said to have studied in Taxila, namely:

- King Pasenadi of Kosala, a close friend of the Buddha,

- Bandhula, the commander of Pasedani's army

- Aṅgulimāla, a close follower of the Buddha. A Buddhist story about Aṅgulimāla (also called Ahiṃsaka, and later a close follower of Buddha), relates how his parents sent him to Taxila to study under a well-known teacher. There he excels in his studies and becomes the teacher's favorite student, enjoying special privileges in his teacher's house. However, the other students grow jealous of Ahiṃsaka's speedy progress and seek to turn his master against him.[17] To that end, they make it seem as though Ahiṃsaka has seduced the master's wife.[18]

- Jivaka, court doctor at Rajagriha and personal doctor of the Buddha.[19]

- Charaka, the Indian "father of medicine" and one of the leading authorities in Ayurveda, is also said to have studied at Taxila, and practiced there.[2][20]

- Chandragupta Maurya, Buddhist literature states that Chandragupta Maurya, the future founder of the Mauryan Empire, though born near Patna (Bihar) in Magadha, was taken by Chanakya for his training and education to Taxila, and had him educated there in "all the sciences and arts" of the period, including military sciences. There he studied for eight years.[21] The Greek and Hindu texts also state that Kautilya (Chanakya) was a native of the northwest Indian subcontinent, and Chandragupta was his resident student for eight years.[22][23] These accounts match Plutarch's assertion that Alexander the Great met with the young Chandragupta while campaigning in the Punjab.[24][25]

See also

- Sharada Peeth

- Nalanda University

- Vikramashila University

- Ancient institutions of learning in the Indian subcontinent

References

- ^ a b c d e Marshall (2013), p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lowe & Yasuhara (2016), p. 62.

- ^ a b Kulke & Rothermund (2004)"In the early centuries the centre of Buddhist scholarship was the University of Taxila."

- ^ Marshall (2013), p. 10.

- ^ Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 50. ISBN 9780984404308.

- ^ Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 255–256. ISBN 9781588369840.

- ^ a b Frazier & Flood (2011), p. 34.

- ^ Altekar (1965), p. 109: "It may be observed at the outset that Taxila did not possess any colleges or university in the modern sense of the term."

- ^ F. W. Thomas (1944), in Marshall (1951), p. 81: "We come across several Jātaka stories about the students and teachers of Takshaśilā, but not a single episode even remotely suggests that the different 'world renowned' teachers living in that city belonged to a particular college or university of the modern type."

- ^ a b "Taxila". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007: "Taxila, besides being a provincial seat, was also a centre of learning. It was not a university town with lecture halls and residential quarters, such as have been found at Nalanda in the Indian state of Bihar."

- ^ "Nalanda" (2007). Encarta.

- ^ "Nalanda" (2001). Columbia Encyclopedia.

- ^ The Pearson CSAT Manual 2011. Pearson Education India. p. 439/ HC.23. ISBN 9788131758304.

- ^ Schlichtmann, Klaus (2016). A Peace History of India: From Ashoka Maurya to Mahatma Gandhi. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. p. 29. ISBN 9789385563522.

- ^ Watters, Thomas (1904-01-01). On Yuan Chwang's travels in India, 629-645 A.D. Dalcassian Publishing Company.

- ^ Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. p. 255. ISBN 9781588369840.

- ^ Malalasekera (1960).

- ^ Wilson (2016), p. 286.

- ^ Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. p. 256. ISBN 9781588369840.

- ^ Gupta, Subhadra Sen (2009). Ashoka. Penguin UK. p. PT27. ISBN 9788184758078.

- ^ Mookerji (1988), pp. 15–18.

- ^ Mookerji (1988), pp. 18–23, 53–54, 140–141.

- ^ Modelski, George (1964). "Kautilya: Foreign Policy and International System in the Ancient Hindu World". American Political Science Review. 58 (3). Cambridge University Press (CUP): 549–560. doi:10.2307/1953131. JSTOR 1953131. S2CID 144135587.

- ^ Mookerji, Radhakumud (1966). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9788120804050.

- ^ "Sandrocottus, when he was a stripling, saw Alexander himself, and we are told that he often said in later times that Alexander narrowly missed making himself master of the country, since its king was hated and despised on account of his baseness and low birth". Plutarch 62-4 "Plutarch, Alexander, chapter 1, section 1".

Sources

- Altekar, Anant Sadashiv (1965). Education in Ancient India (6th ed.). Nand Kishore.

- Frazier, Jessica; Flood, Gavin (2011-06-30). The Continuum Companion to Hindu Studies. A&C Black. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8264-9966-0.

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A History of India (4th ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4.

- Lowe, Roy; Yasuhara, Yoshihito (2016-10-04). The Origins of Higher Learning: Knowledge networks and the early development of universities. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-54326-8.

- Malalasekera, G.P. (1960), Dictionary of Pāli Proper Names, vol. 1, Delhi: Pali Text Society, OCLC 793535195

- Marshall, John (1951). Taxila: Structural remains – Volume 1. University Press.

- Marshall, John (2013). A Guide to Taxila. Cambridge University Press. pp. 23–24. ISBN 9781107615441.

- Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988) [first published in 1966], Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4th ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0433-3

- Wilson, Liz (2016), "Murderer, Saint and Midwife", in Holdrege, Barbara A.; Pechilis, Karen (eds.), Refiguring the Body: Embodiment in South Asian Religions, SUNY Press, pp. 285–300, ISBN 978-1-4384-6315-5