Taharqa

| Horus name | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nebty name | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Golden Horus | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prenomen (Praenomen) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nomen | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| t h r ḳ (Taharqo) in hieroglyphs | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

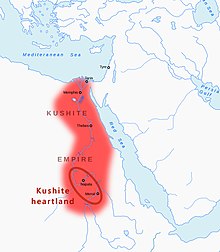

Taharqa, also spelled Taharka or Taharqo (Egyptian: 𓇿𓉔𓃭𓈎 tꜣhrwq, Akkadian:  Tar-qu-ú, Hebrew: תִּרְהָקָה, Modern: Tīrhaqa, Tiberian: Tīrhāqā, Manetho's Tarakos, Strabo's Tearco), was a pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt and qore (king) of the Kingdom of Kush (present day Sudan) from 690 to 664 BC. He was one of the "Black Pharaohs" who ruled over Egypt for nearly a century.[5][6]

Tar-qu-ú, Hebrew: תִּרְהָקָה, Modern: Tīrhaqa, Tiberian: Tīrhāqā, Manetho's Tarakos, Strabo's Tearco), was a pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt and qore (king) of the Kingdom of Kush (present day Sudan) from 690 to 664 BC. He was one of the "Black Pharaohs" who ruled over Egypt for nearly a century.[5][6]

Early life

Taharqa may have been the son of Piye, the Nubian king of Napata who had first conquered Egypt, though the relationships in this family are not completely clear (see Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt family tree). Taharqa was also the cousin and successor of Shebitku.[7] The successful campaigns of Piye and Shabaka paved the way for a prosperous reign by Taharqa.

Ruling period

Taharqa's reign can be dated from 690 BC to 664 BC.[8] Evidence for the dates of his reign is derived from the Serapeum stele, catalog number 192. This stela records that an Apis bull born and installed (fourth month of Season of the Emergence, day 9) in year 26 of Taharqa died in Year 20 of Psamtik I (4th month of Shomu, day 20), having lived 21 years. This would give Taharqa a reign of 26 years and a fraction, in 690–664 BC.[9]

Irregular accession to power

Taharqa explicitly states in Kawa Stela V, line 15, that he succeeded his predecessor (previously assumed to be Shebitku but now established to be Shabaka instead) after the latter's death with this statement: "I received the Crown in Memphis after the Falcon flew to heaven."[11] The reference to Shebitku was an attempt by Taharqa to legitimise his accession to power.[12] However, Taharqa never mentions the identity of the royal falcon and completely omits any mention of Shabaka's intervening reign between Shebitku and Taharqa possibly because he ousted Shabaka from power.[13]

In Kawa IV, line 7-13, Taharqa states:

He (Taharqa) sailed northward to Thebes amongst the beautiful young people that His Majesty, the late King Shabataqo/Shebitku, had sent from Nubia. He was there (in Thebes) with him. He appreciated him more than any of his brothers. (There here follows a description of the [poor] state of the temple of Kawa as observed by the prince). The heart of his Majesty was in sadness about it until his Majesty became king, crowned as King of Upper and Lower Egypt (...). It was during the first year of his reign he remembered what he had seen of the temple when he was young.[14]

In Kawa V: line 15, Taharqa states

I was brought from Nubia amongst the royal brothers that his Majesty had brought. As I was with him, he liked me more than all his brothers and all his children, so that he distinguished me. I won the heart of the nobles and was loved by all. It was only after the hawk had flown to heaven that I received the crown in Memphis.[15]

Therefore, Taharqa says that King Shebitku, who was very fond of him, brought him with him to Egypt and during that trip he had the opportunity to see the deplorable state of the temple of Amun at Kawa, an event he remembered after becoming king. But on Kawa V Taharqa says that sometime after his arrival in Egypt under a different king whom this time he chose not to name, there occurred the death of this monarch (Shabaka here) and then his own accession to the throne occurred. Taharqa's evasiveness on the identity of his predecessor suggests that he assumed power in an irregular fashion and chose to legitimise his kingship by conveniently stating the possible fact or propaganda that Shebitku favoured him "more than all his brothers and all his children."[12]

Moreover, in lines 13 – 14 of Kawa stela V, His Majesty (who can be none other but Shebitku), is mentioned twice, and at first sight the falcon or hawk that flew to heaven, mentioned in the very next line 15, seems to be identical with His Majesty referred to directly before (i.e. Shebitku).[16] However, in the critical line 15 which recorded Taharqa's accession to power, a new stage of the narrative begins, separated from the previous one by a period of many years, and the king or hawk/falcon that flew to heaven is conspicuously left unnamed in order to distinguish him from His Majesty, Shebitku. Moreover, the purpose of Kawa V, was to describe several separate events that occurred at distinct stages of Taharqa's life, instead of telling a continuous story about it.[16] Therefore, the Kawa V text began with the 6th year of Taharqa and referred to the High Nile flood of that year before abruptly jumping back to Taharqa's youth at the end of line 13.[16] In the beginning of line 15, Taharqa's coronation is mentioned (with the identity of the hawk/falcon—now known to be Shabaka—left unnamed but if it was Shebitku, Taharqa's favourite king, Taharqa would clearly have identified him) and there is a description given of the extent of the lands and foreign countries under Egypt's control but then (in the middle of line 16) the narrative switches abruptly back again to Taharqa's youth: "My mother was in Ta-Sety …. Now I was far from her as a twenty year old recruit, as I went with His Majesty to the North Land".[16] However, immediately afterwards (around the middle of line 17) the text jumps forward again to the time of Taharqa's accession: "Then she came sailing downstream to see me after a long period of years. She found me after I had appeared on the throne of Horus...".[16] Hence, the Kawa V narrative switches from one event to another, and has little to no chronological coherence or value.

Reign

Although Taharqa's reign was filled with conflict with the Assyrians, it was also a prosperous renaissance period in Egypt and Kush.[18][19] The empire flourished under Taharqa, due in part to a particularly large Nile river flood, abundant crops,[18] and the "intellectual and material resources set free by an efficient central government."[19] Taharqa's inscriptions indicate that he gave large amounts of gold to the temple of Amun at Kawa.[20] The Nile valley empire was as large as it had been since the New Kingdom.[21] Taharqa and the 25th dynasty revived Egyptian culture.[22] Religion, arts, and architecture were restored to their glorious Old, Middle, and New Kingdom forms. During Taharqa's reign, the "central features of Theban theology were merged with Egyptian Middle and New Kingdom imperial ideology.".[19] Under Taharqa, the cultural integration of Egypt and Kush reached such a point that it could not be reversed, even after the Assyrian conquest.[19]

Taharqa restored existing temples and built new ones. Particularly impressive were his additions to the Temple at Karnak, new temple at Kawa, and temples at Jebel Barkal.[22][23][24][25][26] Taharqa continued the 25th dynasty's ambitious program to develop Jebel Barkal into a "monumental complex of sancturies...centered around the great temple of...Amun."[19] The similarity of Jebel Barkal to Karnak "seems to be central to the builders at Jebel Barkal.".[19] The rest of Taharqa's constructions served to create "Temple Towns", which were "local centers of government, production, and redistribution."[19]

It was during the 25th dynasty that the Nile valley saw the first widespread construction of pyramids (many in modern Sudan) since the Middle Kingdom.[24][27][28] Taharqa built the largest pyramid (~52 meters square at base) in the Nubian region at Nuri (near El-Kurru) with the most elaborate Kushite rock-cut tomb.[29] Taharqa was buried with "over 1070 shabtis of varying sizes and made of granite, green ankerite, and alabaster."[30]

War between Taharqa and Assyria

Taharqa began cultivating alliances with elements in Phoenicia and Philistia who were prepared to take a more independent position against Assyria.[31] Taharqa's army undertook successful military campaigns, as attested by the "list of conquered Asiatic principalities" from the Mut temple at Karnak and "conquered peoples and countries (Libyans, Shasu nomads, Phoenicians?, Khor in Palestine)" from Sanam temple inscriptions.[19] Torok mentions the military success was due to Taharqa's efforts to strengthen the army through daily training in long-distance running, as well as Assyria's preoccupation with Babylon and Elam.[19] Taharqa also built military settlements at the Semna and Buhen forts and the fortified site of Qasr Ibrim.[19]

Imperial ambitions of the Mesopotamian-based Assyrian Empire made war with the 25th dynasty inevitable. In 701 BC, the Kushites aided Judah and King Hezekiah in withstanding the siege of Jerusalem by King Sennacherib of the Assyrians (2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9).[32] There are various theories (Taharqa's army,[33] disease, divine intervention, Hezekiah's surrender, Herodotus' mice theory) as to why the Assyrians failed to take Jerusalem and withdrew to Assyria.[34] Many historians claim that Sennacherib was the overlord of Khor following the siege in 701 BC. Sennacherib's annals record Judah was forced into tribute after the siege.[35] However, this is contradicted by Khor's frequent utilization of an Egyptian system of weights for trade,[36] the 20 year cessation in Assyria's pattern (before 701 and after Sennacherib's death) of repeatedly invading Khor,[37] Khor paying tribute to Amun of Karnak in the first half of Taharqa's reign,[19] and Taharqa flouting Assyria's ban on Lebanese cedar exports to Egypt, while Taharqa was building his temple to Amun at Kawa.[38]

In 679 BC, Sennacherib's successor, King Esarhaddon, campaigned into Khor and took a town loyal to Egypt. After destroying Sidon and forcing Tyre into tribute in 677-676 BC, Esarhaddon invaded Egypt proper in 674 BC. Taharqa and his army defeated the Assyrians outright in 674 BC, according to Babylonian records.[40] This invasion, which only a few Assyrian sources discuss, ended in what some scholars have assumed was possibly one of Assyria's worst defeats.[41] In 672 BC, Taharqa brought reserve troops from Kush, as mentioned in rock inscriptions.[19] Taharqa's Egypt still held sway in Khor during this period as evidenced by Esarhaddon's 671 BC annal mentioning that Tyre's King Ba'lu had "put his trust upon his friend Taharqa", Ashkelon's alliance with Egypt, and Esarhaddon's inscription asking "if the Kushite-Egyptian forces 'plan and strive to wage war in any way' and if the Egyptian forces will defeat Esarhaddon at Ashkelon."[42] However, Taharqa was defeated in Egypt in 671 BC when Esarhaddon conquered Northern Egypt, captured Memphis, imposed tribute, and then withdrew.[18] Although the Pharaoh Taharqa had escaped to the south, Esarhaddon captured the Pharaoh's family, including "Prince Nes-Anhuret, royal wives,"[19] and most of the royal court[citation needed], which were sent to Assyria as hostages. Cuneiform tablets mention numerous horses and gold headdresses were taken back to Assyria.[19] In 669 BC, Taharqa reoccupied Memphis, as well as the Delta, and recommenced intrigues with the king of Tyre.[18] Taharqa intrigued in the affairs of Lower Egypt, and fanned numerous revolts.[43] Esarhaddon again led his army to Egypt and on his death in 668 BC, the command passed to Ashurbanipal. Ashurbanipal and the Assyrians again defeated Taharqa and advanced as far south as Thebes, but direct Assyrian control was not established."[18] The rebellion was stopped and Ashurbanipal appointed as his vassal ruler in Egypt Necho I, who had been king of the city Sais. Necho's son, Psamtik I was educated at the Assyrian capital of Nineveh during Esarhaddon's reign.[44] As late as 665 BC, the vassal rulers of Sais, Mendes, and Pelusium were still making overtures to Taharqa in Kush.[19] The vassal's plot was uncovered by Ashurbanipal and all rebels but Necho of Sais were executed.[19]

The remains of three colossal statues of Taharqa were found at the entrance of the palace at Nineveh. These statues were probably brought back as war trophies by Esarhaddon, who also brought back royal hostages and numerous luxury objects from Egypt.[45][46]

Death

Taharqa died in the city of Thebes[47] in 664 BC. He was followed by his appointed successor Tantamani, a son of Shabaka, who invaded Lower Egypt in hopes of restoring his family's control. This led to a renewed conflict with Ashurbanipal and the Sack of Thebes by the Assyrians in 663 BCE. He was himself succeeded by a son of Taharqa, Atlanersa.

Nuri pyramid

Taharqa chose the site of Nuri in North Sudan to build his pyramid, away from the traditional burial site of El-Kurru. It was the first and the largest pyramid of Nuri, and he was followed by close to twenty later kings at the site.[48]

Biblical references

Mainstream scholars agree that Taharqa is the Biblical "Tirhakah" (Heb: תִּרְהָקָה), king of Ethiopia (Kush), who waged war against Sennacherib during the reign of King Hezekiah of Judah (2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9).[49][33]

The events in the biblical account are believed to have taken place in 701 BC, whereas Taharqa came to the throne some ten years later. If the title of king in the biblical text refers to his future royal title, he still may have been too young to be a military commander,[50] although this is disputed.[51] According to the egyptologist Jeremy Pope, Taharqa was probably between 25 and 33 years old in 701 BC and, following Kushite custom to delegate actual leadership in combat to a subordinate, was sent by his predecessor Shabako as a military commander to fight against the Assyrians.[52]

Aubin mentions that the biblical account in Genesis 10:6-7 (Table of Nations) lists Taharqa's predecessors, Shebitku and Shabako (סַבְתְּכָ֑א and סַבְתָּ֥ה).[53] Concerning Taharqa's successor, the sack of Thebes was a momentous event that reverberated throughout the Ancient Near East. It is mentioned in the Book of Nahum chapter 3:8-10:

Art thou better than populous No, that was situate among the rivers, that had the waters round about it, whose rampart was the sea, and her wall was from the sea? Ethiopia and Egypt were her strength, and it was infinite; Put and Lubim were thy helpers. Yet was she carried away, she went into captivity: her young children also were dashed in pieces at the top of all the streets: and they cast lots for her honourable men, and all her great men were bound in chains

Depictions

Taharqa, under the name "Tearco the Aethiopian", was described by the Ancient Greek historian Strabo. Strabo mentioned Taharqa in a list of other notable conquerors (Cyrus the Great, Xerxes, Sesotris) and mentioned that these princes had undertaken "expeditions to lands far remote."[54] Strabo mentions Taharqa as having "Advanced as far as Europe",[55] and (citing Megasthenes), even as far as the Pillars of Hercules in Spain:[56] Similarly, in 1534 the Muslim scholar Ibn-l-Khattib al-Makkary wrote an account of Taharqa's "establishment of a garrison in the south of Spain in approximately 702 BC."[57]

However, Sesostris, the Aegyptian, he adds, and Tearco the Aethiopian advanced as far as Europe; and Nabocodrosor, who enjoyed greater repute among the Chaldaeans than Heracles, led an army even as far as the Pillars. Thus far, he says, also Tearco went.

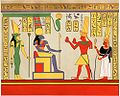

The two snakes in the crown of pharaoh Taharqa show that he was the king of both the lands of Egypt and Nubia.

Monuments of Taharqa

Taharqa has left monuments throughout Egypt and Nubia. In Memphis, Thebes, and Napata he rebuilt or restored the Temple of Amon.[60]

Taharqa in Karnak

Taharqa is known for various monuments in Karnak.

-

Taharqa column

Taharqa column - Kiosk of Taharqa in Karnak

-

Chapel of Taharqa and Shepenwepet in Karnak

Chapel of Taharqa and Shepenwepet in Karnak -

Taharqa's kiosk. Karnak Temple

Taharqa's kiosk. Karnak Temple

Shrine of Taharqa in Kawa

A small temple of Taharqa was once located at Kawa in Nubia (modern Sudan). It is located today in the Ashmolean Museum.[61]

-

The Shrine of Taharqa, Ashmolean Museum

The Shrine of Taharqa, Ashmolean Museum -

Shrine and Sphinx of Taharqa. Taharqa appears between the legs of the Ram-Spinx

Shrine and Sphinx of Taharqa. Taharqa appears between the legs of the Ram-Spinx -

The Ram-Spinx and Taharqa

The Ram-Spinx and Taharqa -

Relief of Taharqa on the shrine

Relief of Taharqa on the shrine -

Taharqa cartouche on the Shrine

Taharqa cartouche on the Shrine -

![King Taharqa and the gods of Thebes. Standing on the left, he offers "a white loaf" to his father Amun-Re, who is accompanied by Mut, Khonsu and Montu, Kawa shrine.[62]](//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/Pharaoh_Taharqa_and_the_gods_of_Thebes._Standing_on_the_left%2C_he_offers_%22a_white_loaf%22_to_his_father_Amun-Re%2C_who_is_accompanied_by_Mut%2C_Khonsu_and_Montu%2C_Kawa_Temple.jpg/120px-thumbnail.jpg)

-

![Taharqa and the gods of Gematen (the Temple of Kawa). He makes an offering to the ram-headed god Amun-Re. Kawa shrine.[63]](//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b8/Taharqa_and_the_gods_of_Gematen_%28the_Temple_of_Kawa%29._He_makes_an_offering_to_the_ram-headed_god_Amun-Re._Kawa_shrine.jpg/120px-Taharqa_and_the_gods_of_Gematen_%28the_Temple_of_Kawa%29._He_makes_an_offering_to_the_ram-headed_god_Amun-Re._Kawa_shrine.jpg)

-

![Taharqa (left) embracing Horus (Re-Horakhty) on the Kawa shrine[64]](//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/01/Closeup_of_Taharqa_embracing_Horus_on_the_Shrine_of_the_25th_dynasty_pharaoh_and_Kushite_King_Taharqa_Egypt_7th_century_BCE.jpg/80px-Closeup_of_Taharqa_embracing_Horus_on_the_Shrine_of_the_25th_dynasty_pharaoh_and_Kushite_King_Taharqa_Egypt_7th_century_BCE.jpg)

Taharqa in Jebel Barkal

Taharqa is depicted in various reliefs in Jebel Barkal, particularly in the Temple of Mut.

-

Taharqa in the Temple of Mut

Taharqa in the Temple of Mut -

Taharqa before the god Amun in Gebel Barkal (Sudan), in Temple of Mut, Jebel Barkal

Taharqa before the god Amun in Gebel Barkal (Sudan), in Temple of Mut, Jebel Barkal -

Taharqa followed by his mother Queen Abar. Gebel Barkal – room C

Taharqa followed by his mother Queen Abar. Gebel Barkal – room C -

Taharqa with Queen Takahatamun at Gebel Barkal

Taharqa with Queen Takahatamun at Gebel Barkal -

Lion-headed God Appademak with Pharaoh Taharqa (right) in the Jebel Barkal Temple of Mut

Lion-headed God Appademak with Pharaoh Taharqa (right) in the Jebel Barkal Temple of Mut -

-

Taharqa making dedications to Egyptian Gods, in the Temple of Mut, Jebel Barkal, Sudan. His name appears in the second cartouche: 𓇿𓉔𓃭𓈎 (tꜣ-h-rw-k, "Taharqa").

Taharqa making dedications to Egyptian Gods, in the Temple of Mut, Jebel Barkal, Sudan. His name appears in the second cartouche: 𓇿𓉔𓃭𓈎 (tꜣ-h-rw-k, "Taharqa").

Museum artifacts

-

Taharqa offering wine jars to Falcon-god Hemen

Taharqa offering wine jars to Falcon-god Hemen -

Taharqa, c. 690-64 BCE, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

Taharqa, c. 690-64 BCE, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen -

Taharqa under a sphinx, British Museum

Taharqa under a sphinx, British Museum -

![Taharqa appears as the tallest statue in the back (2.7 meters), Kerma Museum.[65]](//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/Rulers_of_Kush%2C_Kerma_Museum.jpg/120px-Rulers_of_Kush%2C_Kerma_Museum.jpg) Taharqa appears as the tallest statue in the back (2.7 meters), Kerma Museum.[65]

Taharqa appears as the tallest statue in the back (2.7 meters), Kerma Museum.[65] -

Granite sphinx of Taharqa from Kawa in Sudan

Granite sphinx of Taharqa from Kawa in Sudan -

Serpentine weight of 10 daric. Inscribed for Taharqa in the midst of Sais. 25th Dynasty. From Egypt, probably from Nesaft. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Serpentine weight of 10 daric. Inscribed for Taharqa in the midst of Sais. 25th Dynasty. From Egypt, probably from Nesaft. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London -

Taharqa as a sphinx

Taharqa as a sphinx -

Taharqa close-up

Taharqa close-up -

Pharaoh Taharqa. 25th dynasty of Egypt

Pharaoh Taharqa. 25th dynasty of Egypt -

Shabti of King Taharqa

Shabti of King Taharqa

See also

- List of monarchs of Kush

- List of biblical figures identified in extra-biblical sources

- Takhar (the deity)

- Victory stele of Esarhaddon

- Statues of Amun in the form of a ram protecting King Taharqa

- Sphinx of Taharqo

References

- ^ Bianchi, Robert Steven (2004). Daily Life of the Nubians. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-313-32501-4.

- ^ Elshazly, Hesham. "Kerma and the royal cache". Archived from the original on 3 April 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Clayton, Peter A. (2006). Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. Thames&Hudson. p. 190. ISBN 0-500-28628-0.

- ^ Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05128-3., pp.234-6

- ^ Burrell, Kevin (2020). Cushites in the Hebrew Bible: Negotiating Ethnic Identity in the Past and Present. BRILL. p. 79. ISBN 978-90-04-41876-9. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "Pharaoh Taharqa ruled from 690 to 664 BCE and in all likelihood was the last black pharaoh to rule over all of Egypt" in Dijk, Lutz van (2006). A History of Africa. Tafelberg. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-624-04257-0. Archived from the original on 27 June 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Toby Wilkinson, The Thames and Hudson Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, 2005. p.237

- ^ Kitchen 1996, p. 380-391.

- ^ Kitchen 1996, p. 161.

- ^ Smith, William Stevenson; Simpson, William Kelly (1 January 1998). The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt. Yale University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-300-07747-6.

- ^ Kitchen 1996, p. 167.

- ^ a b Payraudeau 2014, p. 115-127.

- ^ Payraudeau 2014, p. 122-3.

- ^ [52 – JWIS III 132-135; FHN I, number 21, 135-144.]

- ^ [53 – JWIS III 135-138; FHN I, number 22, 145-158.]

- ^ a b c d e Broekman, G.P.F. (2015). The order of succession between Shabaka and Shabataka. A different view on the chronology of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty. GM 245. p. 29.

- ^ "Dive beneath the pyramids of Sudan's black pharaohs". National Geographic. 2 July 2019. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Welsby, Derek A. (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. p. 158. ISBN 0-7141-0986-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Török, László (1998). The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Leiden: BRILL. pp. 132–133, 170–184. ISBN 90-04-10448-8.

- ^ Welsby, Derek A. (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. p. 169. ISBN 0-7141-0986-X.

- ^ Török, László. The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Leiden: Brill, 1997. Google Scholar. Web. 20 Oct. 2011.

- ^ a b Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 219–221. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- ^ Bonnet, Charles (2006). The Nubian Pharaohs. New York: The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 142–154. ISBN 978-977-416-010-3.

- ^ a b Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. pp. 161–163. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ^ Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York: Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-615-48102-9.

- ^ Silverman, David (1997). Ancient Egypt. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-19-521270-3.

- ^ Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York: Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 9–11.

- ^ Silverman, David (1997). Ancient Egypt. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-19-521270-3.

- ^ Welsby, Derek A. (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. pp. 103, 107–108. ISBN 0-7141-0986-X.

- ^ Welsby, Derek A. (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London, UK: British Museum Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-7141-0986-X.

- ^ Coogan, Michael David; Coogan, Michael D. (2001). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 253. ISBN 0-19-513937-2.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 141–144. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ a b Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 127, 129–130, 139–152. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 119. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Roux, Georges (1992). Ancient Iraq (Third ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-012523-X.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 155–156. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 152–153. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 155. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Smith, William Stevenson; Simpson, William Kelly (1 January 1998). The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt. Yale University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-300-07747-6.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 158–161. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Ephʿal 2005, p. 99.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 159–161. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Budge, E. A. Wallis (17 July 2014). Egyptian Literature (Routledge Revivals): Vol. II: Annals of Nubian Kings. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-07813-3.

- ^ Mark 2009.

- ^ Smith, William Stevenson; Simpson, William Kelly (1 January 1998). The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt. Yale University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-300-07747-6.

- ^ Thomason, Allison Karmel (2004). "From Sennacherib's bronzes to Taharqa's feet: Conceptions of the material world at Nineveh". IRAQ. 66: 155. doi:10.2307/4200570. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4200570.

Related to the subject of entrances to buildings, the final case study that allows insight into conceptions of the material world at Nineveh and in Assyria concerns the statues of the 25th Dynasty Egyptian king Taharqa excavated at the entrance to the arsenal on Nebi Yunus. I have argued elsewhere that Egypt was a site of fascination to the Neo-Assyrian kings, and that its material culture was collected throughout the period.

- ^ Historical Prism inscription of Ashurbanipal I Archived 19 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine by Arthur Carl Piepkorn page 36. Published by University of Chicago Press

- ^ Why did Taharqa build his tomb at Nuri? Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Conference of Nubian Studies

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Tirhakah". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Tirhakah". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. - ^ Stiebing, William H. Jr. (2016). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Routledge. p. 279. ISBN 978-1-315-51116-0. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ Pope, Jeremy (2022). "Reconstructing the Kushite Royal House". In Keimer, Kyle H.; Pierce, George A. (eds.). The Ancient Israelite World. Taylor & Francis. pp. 675–92. doi:10.4324/9780367815691-48. ISBN 978-1-000-77324-8.

- ^ Pope 2022, p. 689.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 178. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 162. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ^ Strabo (2006). Geography. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-674-99266-0.

- ^ Snowden, Before Color Prejudice: The Ancient View of Blacks. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983, p.52

- ^ Peggy Brooks-Bertram (1996). Celenko, Theodore (ed.). Egypt in Africa. Indiana, USA: Indianapolis Museum of Art. pp. 101–102. ISBN 0-253-33269-9.

- ^ "LacusCurtius Strabo Geography Book XV Chapter 1 (§§ 1-25)". penelope.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ "L'An 6 de Taharqa" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Cf. D. Meeks, Hommage à Serge Sauneron

, 1979, Une fondation Memphite de Taharqa (Stèle du Caire JE 36861), p. 221-259. - ^ "Taharqa Shrine". Ashmolean Museum. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "Museum notice". 3 November 2017. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ "Museum notice". 3 November 2017. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ "Museum notice". 3 November 2017. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ Elshazly, Hesham. "Kerma and the royal cache". Archived from the original on 3 April 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Sources

- Mark, Joshua J. (2009). "Ashurbanipal". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Ephʿal, Israel (2005). "Esarhaddon, Egypt, and Shubria: Politics and Propaganda". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 57 (1). University of Chicago Press: 99–111. doi:10.1086/JCS40025994. S2CID 156663868.

- Mark, Joshua J. (2014). "Esarhaddon". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson (1996). The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC) (3rd ed.). Aris & Phillips Ltd. p. 608. ISBN 978-0-85668-298-8. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Payraudeau, Frédéric (2014). Retour sur la succession Shabaqo-Shabataqo (in French). pp. 115–127.

- Pope, Jeremy W. (2014). The Double Kingdom Under Taharqo: Studies in the History of Kush and Egypt, c. 690 – 664 BC. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-26295-9.

- Radner, Karen (2012). "After Eltekeh: Royal Hostages from Egypt at the Assyrian Court". Stories of long ago. Festschrift für Michael D. Roaf. Ugarit-Verlag: 471–479.

- Radner, Karen (2015). Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871590-0.

Further reading

- Bellis, Alice Ogden, ed. (2019). "Jerusalem's Survival, Sennacherib's Departure, and the Kushite Role in 701 BCE: An Examination of Henry Aubin's Rescue of Jerusalem". The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures. 19. Lausanne: Swiss French Institute for Biblical Studies: 1–297. doi:10.5508/jhs29552. ISSN 1203-1542.

- Grayson, A. K. (1970). "Assyria: Sennacherib and Esarhaddon (704–669 BC)". The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 3 Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-3-11-103358-7.

- Morkot, Robert (2000). The Black Pharaohs: Egypt's Nubian Rulers. The Rubicon Press. p. 342. ISBN 0-948695-23-4.

![King Taharqa and the gods of Thebes. Standing on the left, he offers "a white loaf" to his father Amun-Re, who is accompanied by Mut, Khonsu and Montu, Kawa shrine.[62]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/Pharaoh_Taharqa_and_the_gods_of_Thebes._Standing_on_the_left%2C_he_offers_%22a_white_loaf%22_to_his_father_Amun-Re%2C_who_is_accompanied_by_Mut%2C_Khonsu_and_Montu%2C_Kawa_Temple.jpg/120px-thumbnail.jpg)

![Taharqa and the gods of Gematen (the Temple of Kawa). He makes an offering to the ram-headed god Amun-Re. Kawa shrine.[63]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b8/Taharqa_and_the_gods_of_Gematen_%28the_Temple_of_Kawa%29._He_makes_an_offering_to_the_ram-headed_god_Amun-Re._Kawa_shrine.jpg/120px-Taharqa_and_the_gods_of_Gematen_%28the_Temple_of_Kawa%29._He_makes_an_offering_to_the_ram-headed_god_Amun-Re._Kawa_shrine.jpg)

![Taharqa (left) embracing Horus (Re-Horakhty) on the Kawa shrine[64]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/01/Closeup_of_Taharqa_embracing_Horus_on_the_Shrine_of_the_25th_dynasty_pharaoh_and_Kushite_King_Taharqa_Egypt_7th_century_BCE.jpg/80px-Closeup_of_Taharqa_embracing_Horus_on_the_Shrine_of_the_25th_dynasty_pharaoh_and_Kushite_King_Taharqa_Egypt_7th_century_BCE.jpg)

![Taharqa appears as the tallest statue in the back (2.7 meters), Kerma Museum.[65]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/Rulers_of_Kush%2C_Kerma_Museum.jpg/120px-Rulers_of_Kush%2C_Kerma_Museum.jpg)